Design and Scale for Engineering Biology

When designing DNA sequences, is it better to use "smart design" or "brute force?" Should synthetic biologists prioritize testing small numbers of carefully designed constructs or large numbers of random or unbiased sequence variants?

Transcript

There's a question that comes up at the beginning of almost every biotech R&D project: "How many designs should we test?" It's a simple question with big implications for how we engineer biology.

First, let me set some context. You're running a R&D project and you need a piece of biotech with a new or improved function. Maybe it's an enzyme or a metabolic pathway. Maybe it’s a vector for gene therapy. Anything useful that can be encoded in DNA.

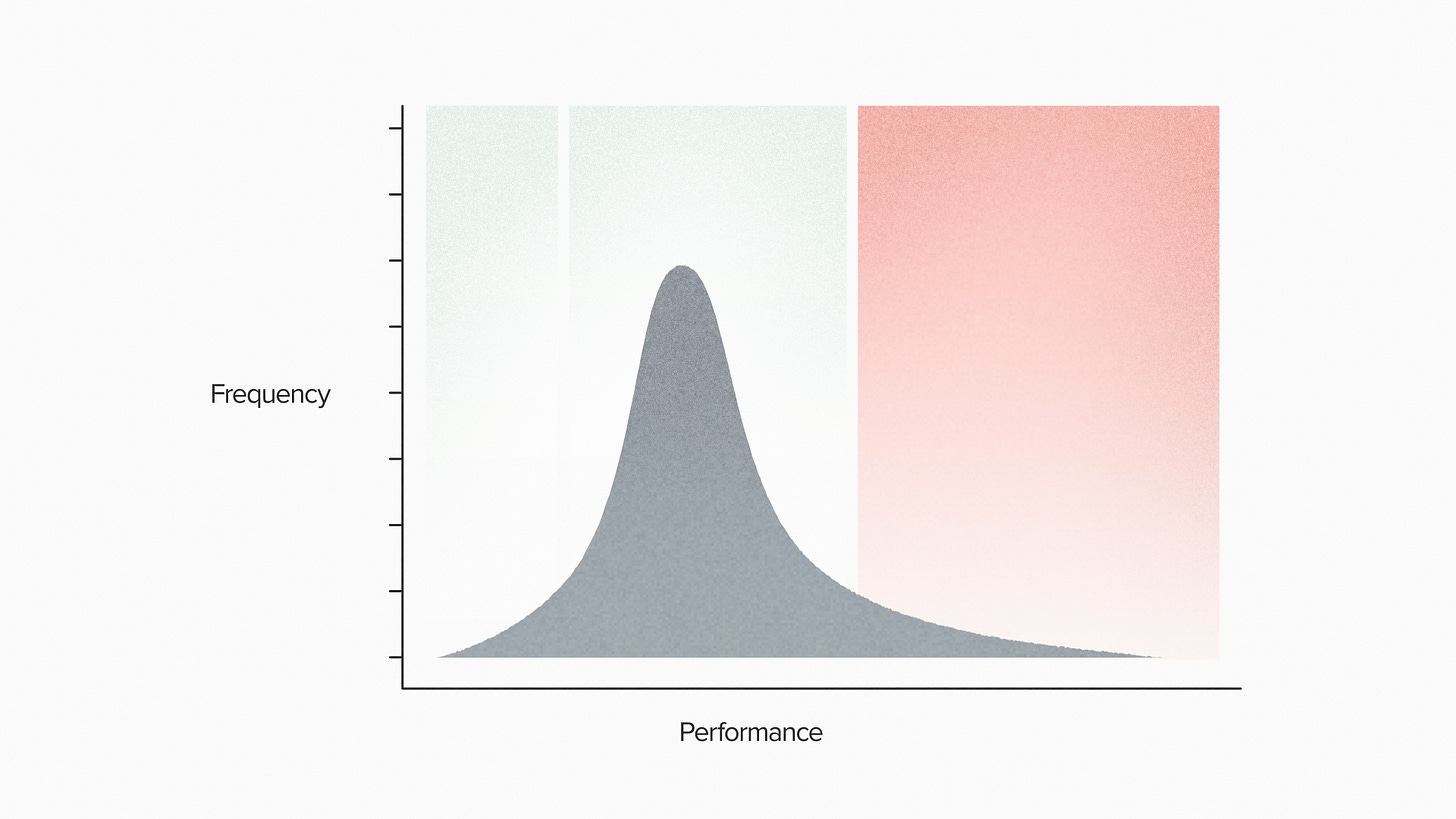

The project probably includes some version of designing DNA sequences, transforming them into living cells and then testing them to see if they do what you want. In a typical case, some DNA sequences won't work. Some of them will work OK. And a small number will be high performers. These sequences code for your high activity enzyme, your selective therapeutic, your superstar cell line.

But how many designs should you test?

It's partially an economic question of risk and reward. More tests means a greater chance of success. More tests means more cost. That's already a good reason to pay attention to this number.

But I actually think it goes deeper than that. It gets to the heart of synthetic biology as a science and what we do here at Ginkgo to make biology easier to engineer. Let me explain.

For some people, the dream of synthetic biology is rational design. In the purest expression of that idea, it means that we can write a DNA sequence and it works exactly as intended on the first try. Other engineering disciplines can sometimes approach this ideal, for example electrical or mechanical engineering. The engineers out there can tell me if their designs really do work perfectly the first time. The point is, it's close enough to be something we can aspire to.

But biology has never quite worked this way. Engineering biology has always required a certain amount of trial and error. Why does biology resist rational design? I'm not really sure. Evolution is a process of variation and selection, so it makes a certain sense that human engineering tends to follow a similar process.

In any case, the upshot is that biological R&D is usually not about trying to get it perfect on the first try. It's about finding the right mix of design and scale. Design to do better tests. Scale to do cheaper tests. And the mix, of course, depends on your goal and the tech you can deploy.

When I worked in a lab, in my pre-Ginkgo days, the right number of tests was usually the number that one person could do by hand. Most biologists out there can relate because almost all of us were trained in this way. 96 tests or less is the right number and it damn well better be because it's the only option.

The automation infrastructure in the Ginkgo Bioworks foundry frees us from this constraint. It allows us to be smarter about lining up the R&D goal with the R&D strategy.

At one end of the spectrum, we can optimize with scale. With the ALE platform, we can do gigantic long-term evolution experiments that search billions of strains. With the EncapS platform, we can encapsulate and screen a hundred thousand strains in ultra-high throughput. Sometimes that's the right answer. We go very big and let nature find the solution for us.

On the other end of the spectrum, we can build carefully designed sequence libraries. Human experts, with computational design tools, choose every nucleotide. These approaches benefit from high throughput automation too. Because we have the capacity to test 100s or even 1000s of strains, we don't have to gamble on any one design strategy. Biology rewards diversity and science rewards large datasets.

So to get back to the original question: "How many tests should we do?" It comes down to the quality of your designs, the efficiency of your scale, and increasingly I think, a secret third thing: AI and training data.

As I write this here in late 2023 we're still early days in AI tech for biology. So forgive me if I get this wrong. But I think it's correct to add AI as a distinct category.

You might think that AI belongs to the design side. Generative AI definitely is a design tool - it can suggest enzyme sequences, for example, that are predicted to have high performance for a given function. We've seen this at Ginkgo. AI can allow us to find high-performance enzymes from 100 tests where other design strategies might require thousands or more.

But those AI-guided designs are only made possible by data at scale. For example, we have large in-house DNA sequence libraries including hundreds of millions of natural proteins. AI foundation models trained on that data can improve our protein designs across many projects.

Or, we can create task-specific models for particular projects. We can design and build hundreds of enzymes, then measure their performance for a given chemical reaction. Feed that assay-labeled data into an AI model and we learn how to optimize DNA sequences for that function.

Because AI uses data to generate better sequences, you could say that it closes the loop between scale and design. The more scale you can access, the better your designs can be.