Humans did not invent biology, biology invented us. The complexity of living systems has long challenged, and humbled, human scientists and engineers. AI is likely to exceed human performance for many biological applications. But is AI a bitter rival or a welcome new tool for exploring the extraordinarily rich and creative living world?

Transcript

Humans did not invent biology, biology invented us. Those of us who work in biotech, we know who's boss. Engineering biology is hard and humans are bad at it. Which, I think, is good news for the humans trying to make biology easier to engineer with AI.

There's a well-known blog post called "The Bitter Lesson" by computer scientist Rich Sutton1. He looks at 70 years of history in AI research and finds a common pattern. When researchers first attempt to build problem-solving algorithms, they start from the wisdom of human experts.

Imagine a chess algorithm inspired by the tactics of a human chess master. Imagine a computer vision system that replicates the anatomy of the human visual cortex. Imagine a speech recognition system that uses concepts from linguistics to divide up the sounds of a word.

It's a reasonable approach. You start from the smartest problem solvers that you have and reformat their ideas into computer code. When this approach succeeds, the experts deserve a share of the credit. The algorithm is just taking their insight and automating it.

The bitter lesson, according to Sutton, is that this doesn't work. At least, it doesn't work as well as approaches that don't make use of human expert knowledge. Instead, more successful approaches use simple operations, general-purpose algorithms, and lots of computation. No human concepts required.

There's an emotional component here. As humans, we might feel hurt when algorithms don't benefit from our knowledge. We might feel a conflict between the human way and the AI way. Who are these algorithms to outperform us? After all, we invented them.

But we don't have to think about AI this way. At least in biology, I think it makes more sense to embrace the idea that AI is not a competitor but a helper. The reason is simple: we kind of need the help.

Humans suck at understanding biology. There I said it. And I say it without much fear that I’m going to offend someone. Because the biologists watching right now are probably nodding their heads harder than anyone like “yeah we do kind of suck.” We're humble like that.

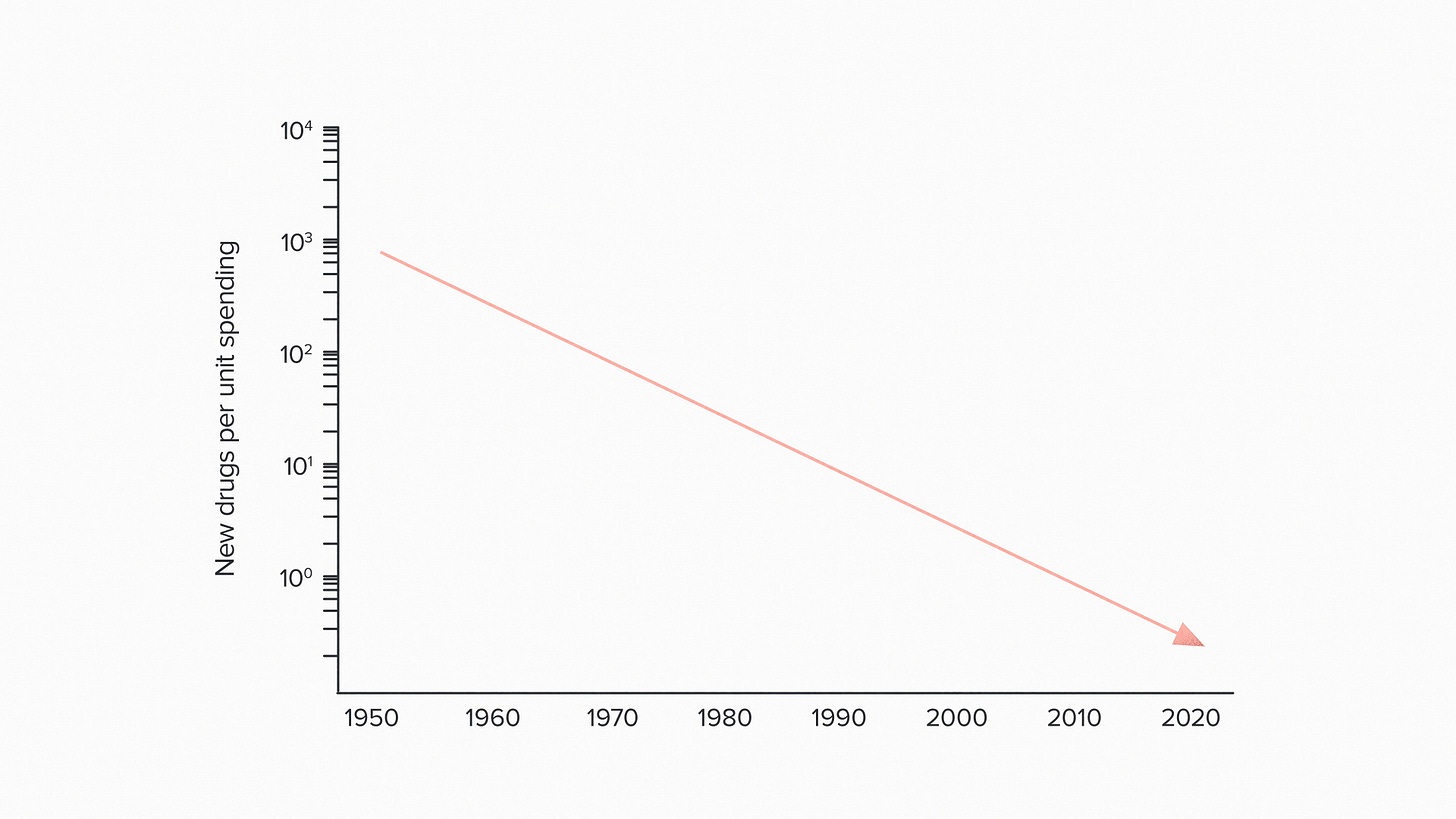

Look, for example, at anything ever written about biomedical research or drug discovery. Key words include long, slow, complex, expensive, risky. We talk about Eroom's law, the opposite of Moore's law, the idea that biomedical R&D gets exponentially harder over time. Biology is hard tech and we know it.

Nevertheless, I’m an optimist. Because all of these challenges are really just opportunities for AI to help us make progress quickly.

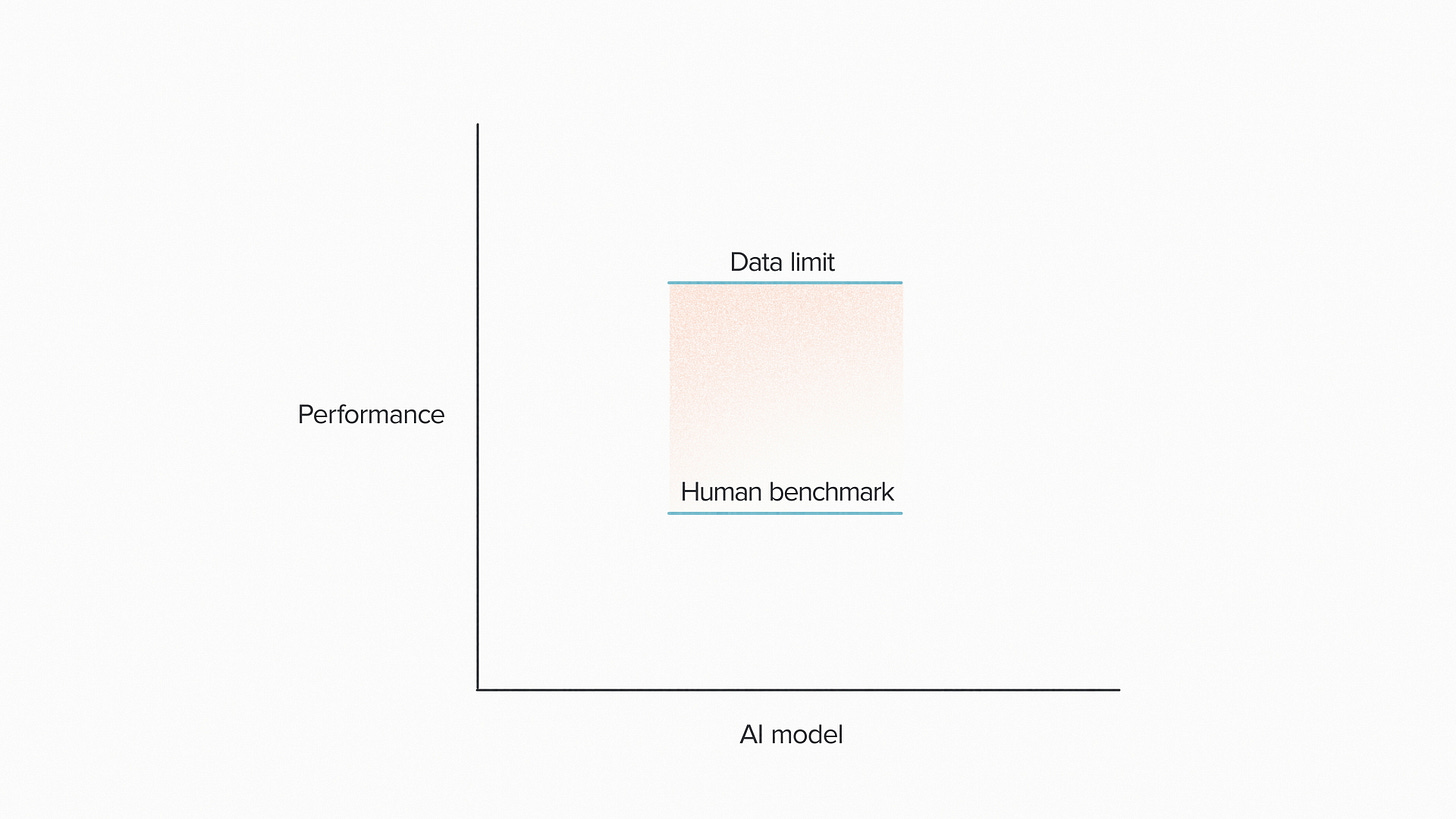

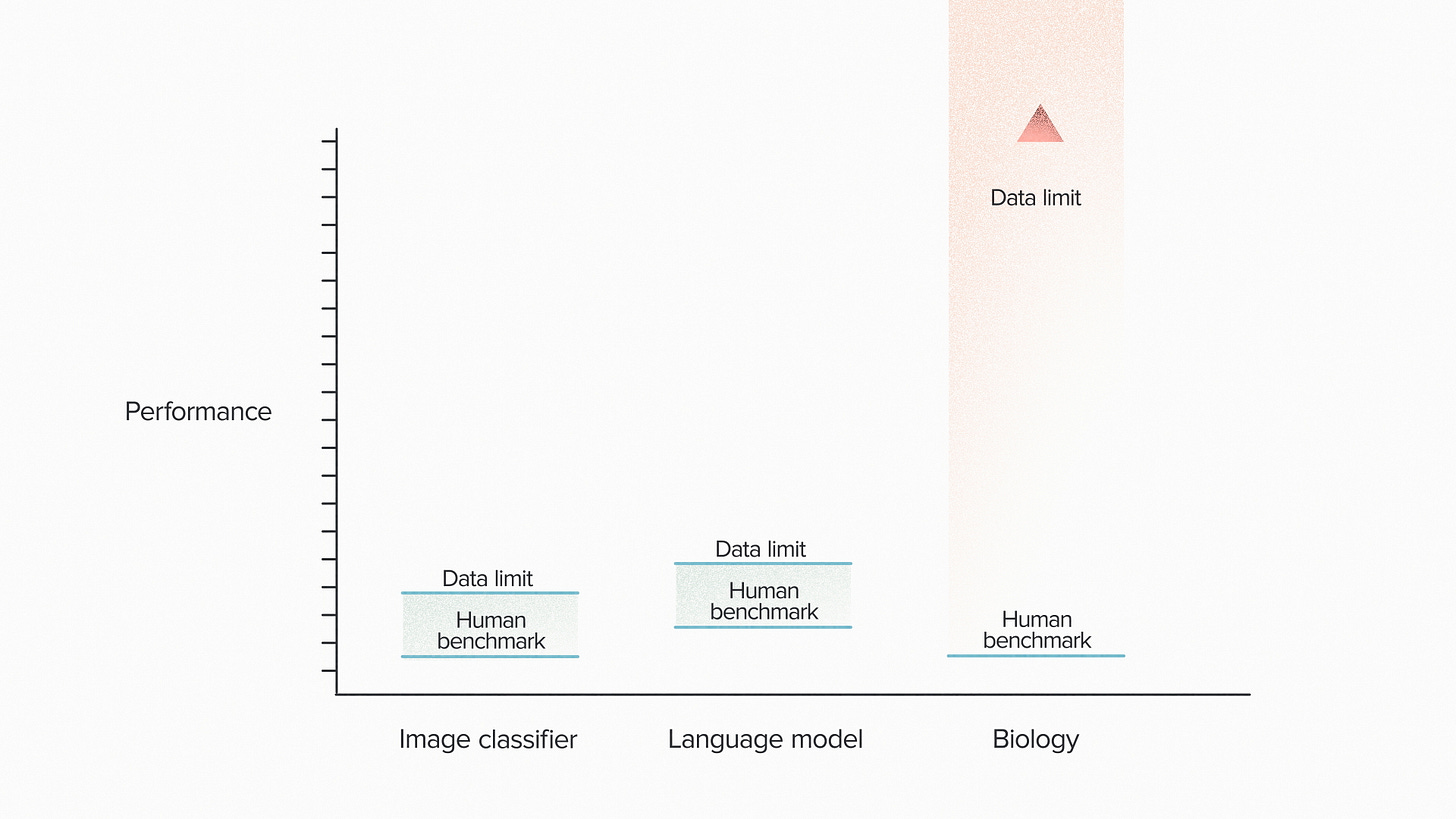

Here’s one way to think about it. The benchmark for success in an AI model is often reaching a human-like level of performance. That’s not always the case. But usually, meeting the human standard is what makes people say “wow” and opens up new applications.

Somewhere above that level, the theoretical limit on the performance of an AI model is often set by the data that it can access or generate. Models learn patterns from data. Their ability to classify, predict or generate is constrained by the data used to train them.

The difference between the human benchmark and the data limit represents a kind of opportunity coefficient, a way of thinking about the boost that humans might get from using AI, with the right data.

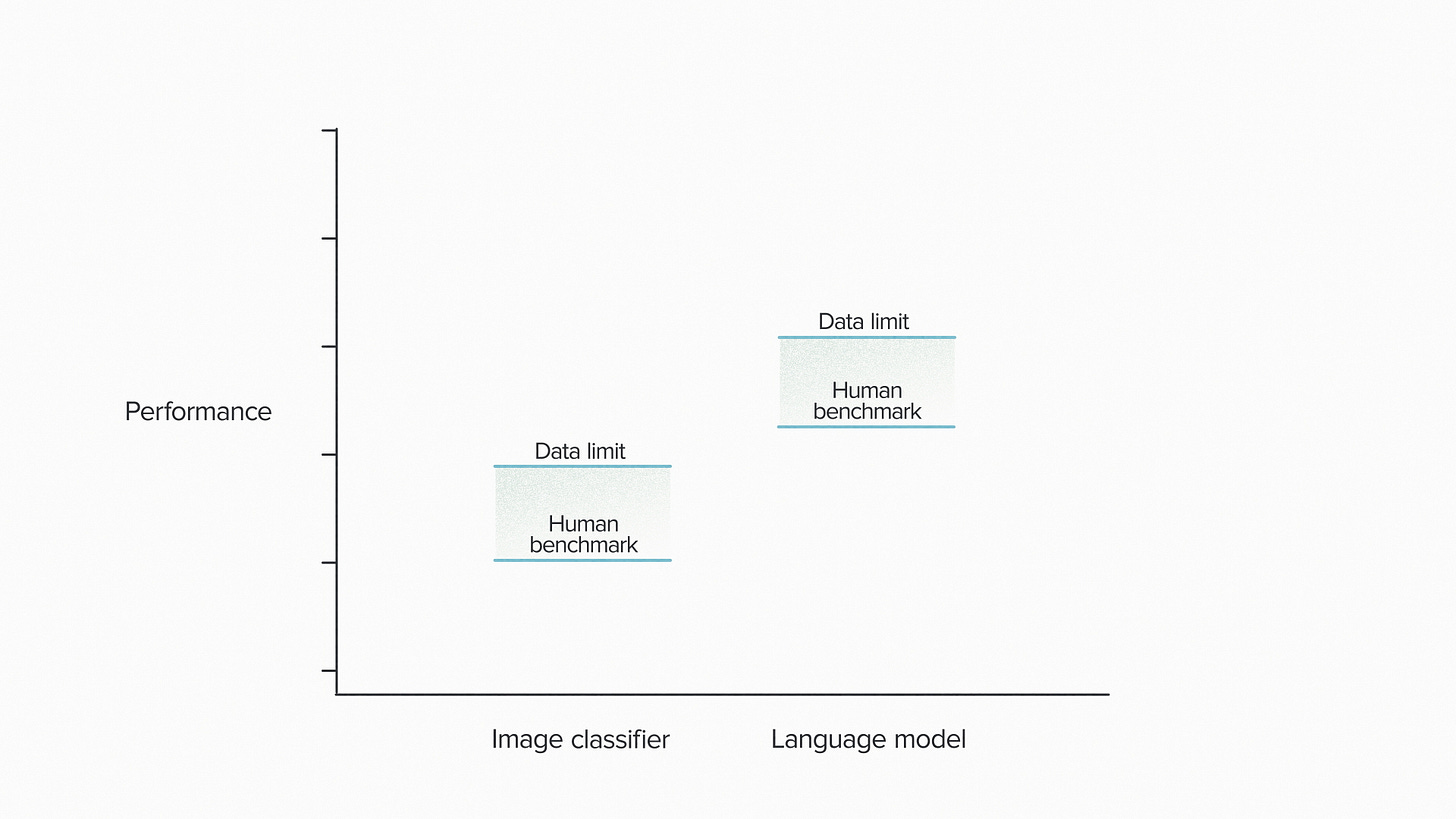

Consider a simple AI tool like an image classifier. Tell the difference between a dog and a cat. Humans are pretty good at this, so we set the bar high. There was a great leap of progress when we saw AI match human performance. More data can make AI even better at this, but there is only so good it can get. A theoretically perfect dog detector is not that much better than what we have today.

For language generation, the task is more complex and the human benchmark is higher. AI models meet that benchmark when they produce human-like text for many typical tasks. The data limit is created by the nature of writing itself, which is fundamentally a human activity. Whatever patterns an AI might learn from training on language, they were created by human writers for human readers. The model can't learn more than we put there.

Now consider biology. The human benchmark is pretty low, we've established that. We suck etc. etc. We already have cases where AI can outperform human experts, for example in predicting protein structures. Rich Sutton would not be surprised by this. It's just the bitter lesson playing out again in another problem space.

But the really interesting thing about biology is the data limit. I can't see it. I don't know where it is. How could I? Because humans didn't invent biology. The creative power of nature is on a completely different level. And yet we can still learn from nature because we have access to DNA sequences and other forms of biological data.

I can't think of any other AI application for which we have data sources that are so incredibly rich and sophisticated, while being not at all human generated. The implications of this are pretty serious - it's a big fuckin' deal.

I can't tell you how to feel about it. You might feel skeptical, because we don't really know yet how hard this is going to be or how much data it will take. You might feel excited, because it seems there might be a powerful new technology coming online. You might feel nervous, because we have to ensure that we use it with care. You might feel bitter, because here is yet another space where AI can outperform humans.

Or you might feel, like I do, humble. Nature has always been more complex and creative than we are. I'm used to it. I never expected to understand biology completely, so AI to me feels like a welcome new tool and not a competitor. From where humans are today to where nature lives, I see a lot of room to grow. And that makes me feel hopeful.