Fitter Microbes Faster with Automated ALE

Evolution is what microbes do best - they adapt to local conditions and they thrive. If you're developing an industrial process that uses microbes, that might be exactly what you want. Today we’re talking about some foundry tech for enhancing microbial fitness with evolution.

Transcript

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution, or ALE, is the process of evolving microbes in a controlled laboratory environment. Here at Ginkgo Bioworks, we use automated ALE instruments to make this process faster and more reliable. This is proprietary tech, many years in the making, that we acquired in 2022. I want to illustrate what it can do with an example.

Let's say you want to produce something valuable using fermentation - a protein or a fine chemical. So you have a microbe - maybe it’s a common yeast strain, maybe it’s a more unusual bacterium that you isolated from the soil. Maybe it’s the product of synthetic biology - a microbe we made for you here at Ginkgo. You get the idea - any old microbe.

You have a feedstock that you’re going to give them as a growth medium. You’re not made of money and you know that microbes aren’t picky about their food - so this feedstock might be something pretty cheap. Maybe it has an unusual mix of nutrients or other features that are less than ideal: low pH, salt, growth inhibitors, whatever.

When you grow that microbe on that feedstock, you probably aren't getting the highest possible productivity. Because that microbe has never seen that feedstock before. It isn't adapted to that environment.

Evolution is the solution. Our automated ALE system allows evolution to happen under ideal conditions. That means faster and more consistently. Here’s how it works.

We start with a microbial culture. These are your microbes growing in your feedstock or whatever growth media you want to evolve them in. We hook up some tubes. There’s an input tube to supply fresh media. There’s an output tube to take away waste. There’s an air line to control the oxygen levels.

As the microbes grow, we track the density of the culture. Because the medium becomes cloudy as the microbes multiply, we can measure the growth with simple optics.

As the cell density increases, the ALE system drains out some of the culture and replaces it with fresh media. Effectively we’re monitoring the growth rate and adjusting the dilution rate to match. We want a large population of cells and a fast generation time to maximize the rate of evolution.

Within the culture tube, mutations emerge spontaneously, some of which improve the fitness of the cells. A mutant might use nutrients more efficiently, might be more tolerant of hard conditions, or something else that improves the overall growth rate. Every time the culture is diluted, the faster growing mutants increase their share until eventually they represent the entire population.

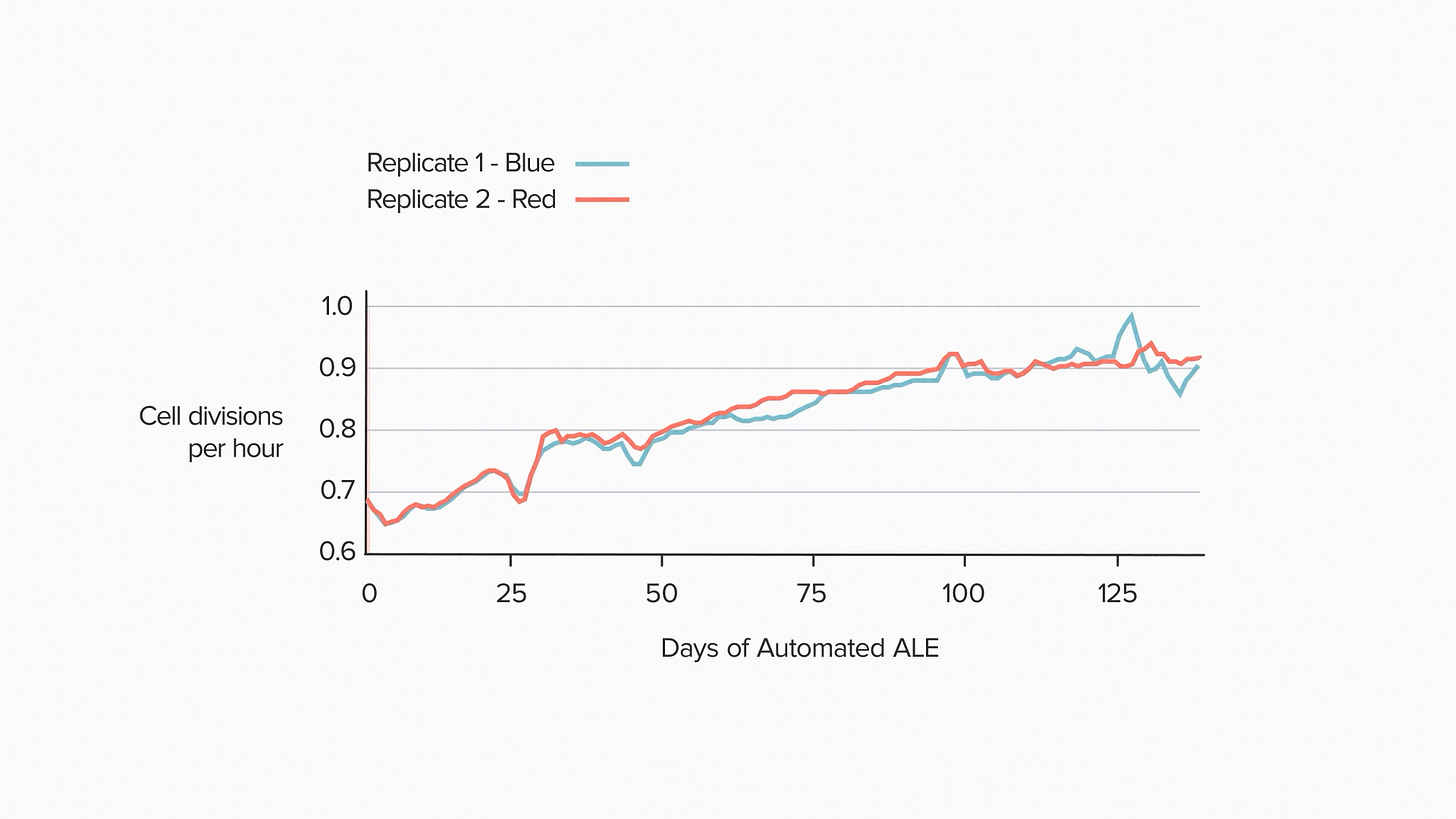

Here's an example showing the growth rate over time for a population of microbes under ALE. Mutations are happening at random. They accumulate over time. The natural drama of the survival of the fittest plays out again and again for as long as beneficial mutations continue to arise. In this particular run, we saw the growth rate increase by about 30% in about 4 weeks.

Those numbers are probably a little faster than is typical. Of course, how much improvement we see and how quickly depends on the microbe and the conditions. But as a rule of thumb - evolving a microbial population takes hundreds or thousands generations and 3-6 months.

The best way to see the advantages of automating ALE is to compare it to approaches that don’t use automation. Once upon a time, the only way to do this was to have a human do it by hand. I’ve done it myself. You take a sample with a manual pipette and back-dilute it into a fresh batch of media once or twice a day.

With the manual technique, the microbes are allowed to grow to saturation in between dilution events. When they stop growing, they stop evolving. Let's say, for example, you did a manual dilution of 1:100 every day, including weekends, for the duration of the experiment. It takes a little more than 6 divisions for the cell population to increase by a factor of 100. In the automated system, we might see 24 generations per day for a typical microbe. That's about 3 and a half times faster evolution.

The automated system can also reduce human error. I’m a pretty good scientist and diluting microbes is as simple as it gets. I don’t know what my error rate would be in doing that by hand. Maybe 1%. But manual ALE can require hundreds of serial transfers. Those human error rates compound exponentially. A 99% success rate for a single transfer drops to a 37% success rate when you have to do it 100 times in a row.

This is the secret sauce for a good automated ALE system. Moving liquids around is simple. Doing it with no errors for 1000 operations requires many subtle optimizations that took years to perfect.

Here's what that looks like in practice. New microbes. New feedstock. This time we're showing results from two different ALE devices to highlight the consistency. Evolution is remarkably steady for about 100 days. Then the growth rate levels off. No further mutations appear to change the fitness. The population stabilizes.

With the ALE instrumentation in place, it’s easy to adapt the program to support different evolutionary outcomes. For example, maybe you’re looking to evolve tolerance to a particular kind of stress like low pH. We can drop the pH slowly over time, automatically adjusting the selective pressure to match what the microbes can tolerate. We want enough stress to favor the evolution of tolerance, but not so much that the cells stop growing.

Or maybe you want to improve your microbe's growth on a new type of nutrient or feedstock. If you only offer the cells that nutrient, they’ll die before they can evolve. But if you alternate the new media recipe with an old one, you create the ideal conditions for evolution to occur.

We can combine ALE with genetic engineering when we introduce a new metabolic pathway. We get the cells growing at a base level, then let evolution take the wheel. Human engineers don't always understand the subtle changes needed to optimize an engineered capability. But evolution will find them, so long as they contribute to improved fitness.

Or we might use automated ALE just on its own, with no genetic engineering required. There are so many microbes out there, so many feedstocks, so many stress conditions. Almost every bioprocess is going to benefit from a well adapted microbe.

Automated ALE gives evolution the space to really cook.

Can you use it to adapt E. coli to grow on alternate carbon sources? Like maybe methanol?