Better Food Proteins with EncapS

It takes a high-performance microbe to manufacture food proteins through fermentation. The EncapS platform in the Ginkgo foundry can screen in ultra-high throughput, allowing us to find superstar microbes even without targeted genetic modification.

Transcript

Let's take a closer look at a project that we did here at Ginkgo Bioworks for a customer in the food space. Can I just say that I love the expression "food space?" It makes me feel like a hungry astronaut.

Anyway this customer was looking for a microbe to make a protein. This particular protein was a food ingredient. So of course we knew we needed to use a food safe microbe and a food safe production process. That's no big deal, we do that all the time.

We also knew, as is often the case out there in food space, that we'd be going for the highest possible yield of this protein from fermentation. That's because food ingredients are usually pretty price sensitive. The difference between a good yield and a great yield goes straight to your cost of goods sold and can determine whether the customer's production process is profitable.

Going in, we felt confident that we could to that. Of course not all proteins are alike, not all production processes are alike, but we're usually pretty good at getting those protein yields up to the next level. And in this case that's exactly what we had to do, because the customer had already engineered a bioproduction strain for this protein, and it wasn't meeting their targets.

So how do you go from a good bioproduction strain to a great one? For this project, we went with the EncapS technology. That stands for encapsulation and screening. This is an unbiased method for artificial selection. No targeted genetic engineering required. Instead, we start with a large population of random mutants, essentially natural variation, and we use the EncapS system to package them into tiny little droplets that we call nanoliter-scale bioreactors.

EncapS can separate out a large number of these droplets in a small space. The microbes grow inside the tiny droplets and secrete their protein. Then, still inside the droplet, we can measure the amount of protein production using a laser and sort out the microbes that are making the most protein.

The power of EncapS is in the sheer number of tests that we can do. For this project we tested 200,000 strains per run and did 3 iterations. Even with a lot of automation, you wouldn't be able to test that many strains without this machine.

I also like EncapS because it doesn't require any genetic engineering or DNA design. I know that sounds weird to say, because I love genetic engineering and DNA design. But EncapS plays really nicely as a complementary approach. It finds improvements that are anywhere in the genome, including ones far away from any engineered DNA.

The mutations that we find with EncapS can improve strain performance in complex and holistic ways, including ways we probably couldn't find on purpose. Think about the overall strain health, metabolism, and in this case the machinery of protein production. It's a process much like natural evolution, life finds a way. If we can select for it, we usually get it.

And that gets me to the hardest thing about EncapS, which is the selection part. In order to select the high performance strains, we first need to be able to measure the property that we're trying to improve. Doing that inside a nanoliter scale droplet is not always easy.

For this particular project we had to develop a custom assay to measure the customer's protein. There's really no way around that. You have to be able to measure something before you can improve it. But we don't always have to start from scratch.

EncapS uses fluorescence-based assays, which are pretty common in biotech. So we often find that an assay already exists that just needs to be scaled down. Or for simpler products we may have an in-house assay ready to go.

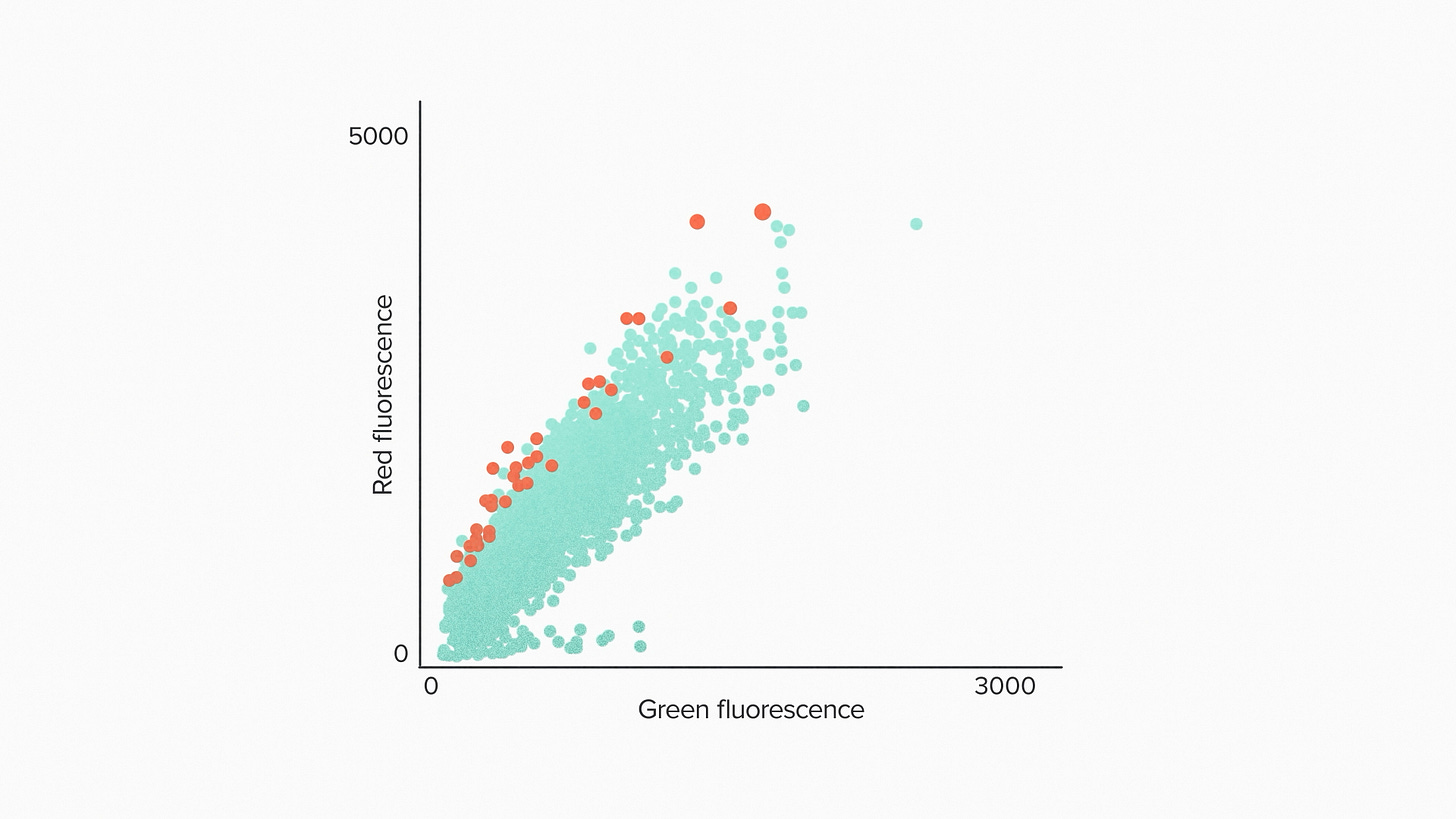

Let's take a look at the results. Here we're showing test results for 200,000 strains. The horizontal axis corresponds to the total number of cells within a droplet. The vertical axis corresponds to the secreted protein. A top performer is going to have a lot of protein relative to the number of cells, so we sorted out those points along the top of the curve.

After 3 iterations of this we had a strain that increased the secreted protein production by 50%. And this is on top of the strain that we started with, which had already been engineered for protein production. Some other key stats on this project: the EncapS screen took about 4 months. The total project of delivering a commercial production strain to the customer was done in less than a year.

EncapS is very versatile. We can put almost anything in these droplets: Bacteria, yeast, filamentous fungi, even mammalian cells. And it's a completely different approach to solving problems than targeted genetic engineering. So if you want to improve a phenotype without genetic engineering, you can do that. Or if you combine this strategy with genetic engineering, like we did here, you can take your strains to the next level.